The Irrawaddy Magazine |

| Dateline Irrawaddy: Sexual Abuse and Stigma Posted: 16 Dec 2017 12:27 AM PST Kyaw Kha: Welcome to Dateline Irrawaddy! This week, we'll discuss an alarming increase in child rape cases in Myanmar. Daw Myat Sandar Thet, the founder of Myintmo Mitta, a refuge for single mothers, and Lway Poe Ngeal, general secretary of the Women’s League of Burma (WLB), which is a coalition of 13 women's ethnic organizations, will join me for the discussion. I'm Irrawaddy Burmese reporter Kyaw Kha. The situation of sexual abuse of children is bad in Myanmar, and I'm sure no one wants to see such news. According to official government figures, there were 85 reported cases of molestation of girls between 6 and 10 years old in 2016. That number is currently at 79 for 2017, so it is not declining. Mya Sandar Thet: You said the situation was bad based on government data but the situation on the ground is likely much worse. According to my experience as a volunteer, only one in four child rape cases is reported to the police and a trial is ordered. We should understand that sexual abuse of children is much worse [than the government data shows] in Myanmar. That data also only includes girls older than six. In reality, there are cases of abuse to girls of one and two years of age. If we include those ages and the cases that go unreported, the situation is much worse. We need to alert people to this. If you ask me when child rape cases are likely to occur, it is when there is not close contact between parents and children. KK: How bad is the situation in ethnic areas? Lway Poe Ngeal: It is not safe for women and girls anywhere. Girls fall victim amid clashes in conflict areas in ethnic regions but they also fall victim to those in power in non-conflict areas. According to our survey, child victims include girls above three. No matter how we protect ourselves, there is no security. We are seeing that cases happen almost every day in Myanmar. In the past, most rape cases were committed by the Tatmadaw and armed ethnic groups. Today, such cases have not declined and what's worse is that the number of rape cases committed by civilians has also increased. KK: In child rape cases, victims and their families might not be willing to report to authorities because of humiliation. What are the difficulties to bringing those cases to court as well as throughout the trials? MST: Before a case is brought to court, the child victim will be brought to the hospital and police station first. The police station will bring the victim to the hospital. There the doctor will check whether there was a rape. The psychological trauma of the child will be eased if the doctor can consult skillfully to help them avoid reliving the ordeal. And when the case is brought before the court, the public perception is that awkward questions will be asked at the trial. In fact, lawyers can ask the victims questions in writing on paper. Psychological trauma to the young victims can be largely prevented at the hospital and at court. I think these two places can help a lot in easing the psychological trauma of child victims. KK: What do you think Lway Poe Ngeal? LPN: I would like to point out two points. Daw Myat Sandar Thet talked about going to court. But not every place in Myanmar has a court, especially in ethnic areas. According to the Penal Code, there must be a medical report [forensic evidence] for a rape case. But in ethnic areas, women are raped, for example while chopping sugar cane and firewood in the forest. There is no clinic or doctor. So, how can we get forensic evidence? I am talking about difficulties rape victims experience before and after their cases are brought before a court. As I've said, it is difficult to get forensic evidence for legal proceedings. In ethnic areas we can't report directly to police. As there are no police, we have to report to the village head or administrator. Once the case is brought to them, it usually disappears there, and is never brought to the court. Another thing is the court is in the town and transportation is very difficult. There are villages that have not seen newspapers and radio, far from knowing what media is. Victims from such remote areas can't afford to go to the town or stay in the town during the trial. They have a lot of difficulties. Again, it is very difficult to take action against rapes and sexual abuses committed by those in power such as the Tatmadaw and armed ethnic groups. KK: We've barely seen efforts or action to address this issue. What remedial actions should be taken? Who should be involved in remedial efforts and to what extent do you think the government should be involved? MST: Most child rape cases are acquaintance rapes committed by those who are close to the victims—either their family members or neighbors. According to my experience, there is hardly a case in which a stranger grabs a girl by the roadside and rapes her. As most of the cases are committed by family members and neighbors, I think pulling the child victim out of her community for a while would help a lot to ease psychological trauma. Then, the victim can be sent to another place to receive schooling, perhaps to a boarding school. Myanmar people typically are easy to forget and forgive, so if the child comes back to her home with some achievement, for example after finishing university, she should be able to live a normal life again. Otherwise, suppose a child were raped by her own father and continued to live in that house. It would make the mother and child feel very uneasy. And, the father will feel too guilty to look at his daughter, and the daughter dare not look at the father, who is her rapist. I have seen some incest cases in which a brother raped his sister. I was terribly shocked by such cases, wondering how the parents could face them. Under such circumstances, those children should be pulled out of that environment temporarily and a new environment should be created for them. If the concerned family can't take that responsibility, then the government should take it. If not the government, associations and agencies connected with the government such as the Maternal and Child Welfare Association or the Myanmar Women Entrepreneurs Association should focus their attention on child rape. Though this responsibility falls on the government, it would be inadvisable for it to gather child rape victims and send them to a particular school. If the government does so, it will only create a closed community of child rape victims. And I don't want them to grow up amid trauma. If possible, victims from hilly regions, for example Christian children, should be able to come to the plains and start a new life. The government should create new families and safe environments for them and enable them to purse school and vocational education. But if it gathers the victims at a particular place, they will be viewed by the people as a group of child rape victims and it will be very hard to erase that view. We should therefore create a comfortable and supportive environment that resembles a new family for them. This issue seems to be easy to handle, but we must be aware that it is delicate. LPN: There are laws that prevent child rape and provide support to rape victims. There are international laws. Myanmar has ratified, for example, CEDAW, but has not implemented it. The international community is responsible for this. It should keep putting pressure on this country to implement the agreements it has signed. The government is responsible to implement what is has signed. We also need to have awareness and knowledge. Besides knowledge about reproductive health, we should also be aware of gender issues and have some knowledge about international laws and what laws our country has ratified. If individuals have such knowledge, then we'll be able to reduce rape cases gradually, and of course, on condition that there is rule of law. KK: Lway Poe Ngeal has talked about how to prevent child rapes. What actions do you think should be taken to prevent them? MST: I would educate the men first. Then, I'd give sex education. And thirdly, there is a need to correct a popular misconception of mothers. In our society, usually mothers tell their young daughters that their private parts are a source of shame. But when the child has grown up, then the mother tells her to value it. So the child is confused, and she can't consult the problem with her mother. So, pregnancies occur as a result. Therefore, we need to rebuild the relationships between mothers and daughters, and fix the morals and ethics of males. And sex education should be last. People think sex education is important. But personally, I think it is not as important as the morals of men. If males have high morals, sex education is the last thing to do. KK: Thank you for your contributions. The post Dateline Irrawaddy: Sexual Abuse and Stigma appeared first on The Irrawaddy. |

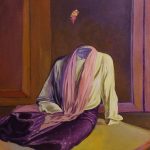

| Artist Min Zaw Aung Inspires Viewers to Think Outside the Box Posted: 15 Dec 2017 09:47 PM PST Min Zaw Aung has grown to hate ordinary creations and has looked for something different. He has painted a girl but was not satisfied. So, he changed her eyes to those of a snake and dressed her in snakeskin. "The eyes of this girl resemble those of a snake. They captivate," he said.

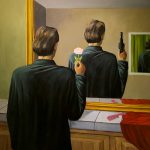

In another painting, a person is holding a flower but in his reflection in a mirror, a gun is in his hand instead. "In social interaction, people think other people will respond the same way if they are good to them. But not every person will be good back to you even though you are nice to them," he said. "I don't want to draw complete figures like in realism. I want to leave something to the imagination for viewers. I want inspire them to think beyond," said Min Zaw Aung, the 32-year-old artist from central Myanmar. Though he is particularly keen on surrealism, most of his paintings describe Buddha's philosophies, as he used to live in a monastery with his relative monks for many years.

Since graduating from Yangon National University of Art and Culture in 2007, he has participated in several group art exhibitions. But he has organized his first exhibition only recently at Bo Aung Kyaw Street Art Gallery. About a sitting man whose shadow is much larger than his actual physical body, he said: "Sometimes, the real is small and placed in the back seat." The artist is displaying most of early works at the exhibition 'In My Memorial,' which will be held through Tuesday. More than 20 paintings are on display and can be purchased for US$150 to $1,600.

"Min Zaw Aung has created his works with boldness, confidence and great creativity, and I found no fear or nervousness in his paintings unlike the works of surrealist painters in the past," said artist Myat Kyat. The post Artist Min Zaw Aung Inspires Viewers to Think Outside the Box appeared first on The Irrawaddy. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Irrawaddy. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |